My dad passed away at the age of 50, after a short and brutal fight with anaplastic thyroid cancer. It’s been 15 years, and just writing those words still guts me. My dad and I didn’t have the easiest relationship, but he was the center of my universe in every way that mattered. He was that for a lot of people. He had an iron will and an unbending conviction so strong that they created their own gravity.

The death that took him seemed impossible. Even with the median life expectancy for his diagnosis being only four months, it felt inevitable that he would beat the odds. I know everyone says that their dad is the strongest person they know, but mine was truly made of tougher stuff. Through sheer grit and unrelenting determination, my dad clawed his way out of a childhood of unimaginable trauma and poverty to become a doctor, giving his children a life that must have seemed unreachable when he began that climb. He would overcome this, too.

A week after completing 30 grueling days of radiation, he was finishing up a five mile run on the treadmill in the basement when we got the call. The cancer had spread. There was nothing left to do. We were told that if he was lucky he might have two years left. He died at home two weeks later, surrounded by his wife and children.

I’ll be forever grateful for that last week, before he started to slip away from us — before the hospice nurses and the hushed late night vigils listening to him struggle to breathe. In that last week he was just my dad, and we spent hours driving down country roads in his Jeep or sitting at a picnic table at his favorite shooting range talking and grappling with the inevitability of what was to come.

My dad had the soul of a philosopher, and the existential nature of his death was as fascinating to him as it was terrifying. “Time is an illusion,” he told me on one sun-dappled afternoon. “We perceive it as moving in only one direction, but in reality, everything is happening at once. On the part of our individual timelines that overlap, we’ll always be together. And when I’m not with you anymore, I won’t really be gone. I’m just right around the corner.”

Just around the corner…

For the last 15 years, I’ve often imagined my dad that way — waiting just around the corner. I was terrified in those early days that he would start to fade for me, but he never has. I can still summon his face, his voice, the sound of him playing his guitar quietly in the living room late at night after everyone had gone to bed. He visits me in dreams. We still fight. I’m not a particularly spiritual person. I don’t believe in ghosts. But it’s clear to me that, in a very real way, the people that we love live on inside of us.

He lives on in my younger siblings, as well — though their experience has been very different than mine. I was 20 when my dad passed, but his youngest were five, three, and one years old. Over the years it’s become almost impossible for my sisters to distinguish between which flashes of memory they have of him are real and which are just stories that have been told to them again and again — a part of their own personal mythology. For my brother, who was only a baby, it’s almost as if my dad never existed.

Except that it’s not.

Every year on his birthday and on the anniversary of his death, we make the pilgrimage to the waterfall in the Hocking Hills where our dad’s ashes were scattered. Before he died, this short hike was one that we made often as a family. It’s easy to feel his presence there under the mossy cliffs. And though they don’t remember him except for in pictures and stories, my little siblings feel the same heartbreak and the same hole in their lives where he was meant to be.

We thought we’d have more time…

The biggest regret of my life is that we didn’t do more to preserve the memory of my dad for my siblings before he died. He’d planned to write letters to the kids, to record videos for them, to leave them messages of love and some kind of window into the man who had been their father. We thought we’d have more time.

We do what we can to keep his memory alive for them, but pictures are not the same as being able to hear his voice in their heads saying that he loves them. I can tell them how proud he would be of the amazing, compassionate, hilarious people that they’ve become, but I would give anything to go back in time and have the chance for him to tell them himself about his dreams for them.

My dad died the year before the first iPhone came out. It was a different time, before everyone had a device to record video in their pocket — and my dad was never much of one for being in front of the camera. Very few videos of him exist, and nothing that does much to paint the picture of the man that he was.

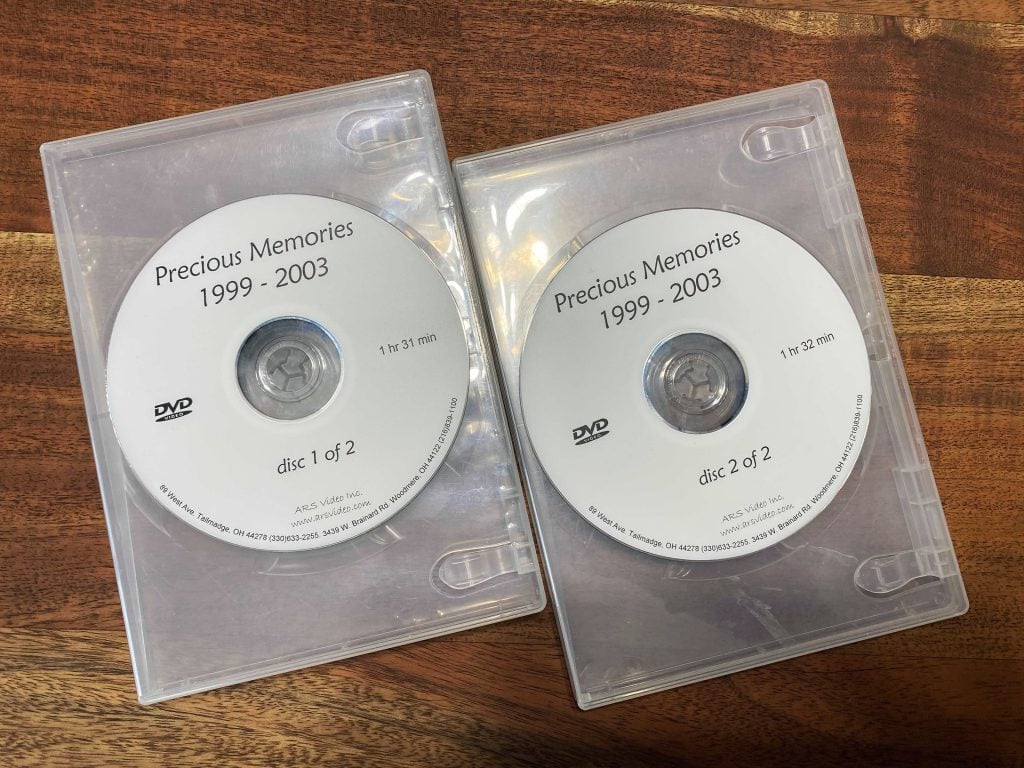

Five years ago, my aunt surprised us with two DVDs of videos, each an hour and a half long, that she had taken when my sisters were babies and she was their caregiver during the day. “Your dad is on these,” she said. “I don’t want you to get too excited, because he’s not in there much, and he’s mostly in the background, but he’s there.” I sobbed when she handed them to me.

Anyone who’s lost someone they love knows the crushing weight of the finality of death — the ache of knowing that there won’t be even one more moment together. Being handed those videos was like opening a portal into a reality where I got to have a few more moments with my dad. Even if it was just a glimpse of him — refilling his coffee, reading a book, stringing his guitar — to have him peek back around the corner, even for just a moment, felt like more powerful magic than I knew how to handle.

I still haven’t watched those old videos. I’m not sure if I ever will. I keep waiting for it to feel like the right time, but as long as they remain unwatched, it feels like I still have a few more minutes with him. I don’t know if I’ll ever be ready. I don’t think anyone is ever ready.

Becoming the family archivist

The sudden and unexpected loss of someone you love has a way of sharpening the focus on one of life’s painful realities; You never know how much time you have left. This realization has inspired me to be more intentional about capturing and preserving the moments that matter most with my loved ones — to become my family’s archivist.

Like anything worth doing, it takes time and planning. Here are some of the things you can focus on if you’d like to do the same.

Take Pictures (And Videos) Of The Small Stuff

There are the moments in life where it’s a no-brainer to take photos and videos, like baby showers, graduations, birthdays, and weddings. But the moments that you’re most likely to wish yourself back to are the small moments with the people you love where you’re just hanging out and being yourselves.

Try to get in the habit of noticing these moments and grabbing your smartphone or camera to capture it, even if it’s just one photo or a quick minute-long video. Years later when you look back at them, you’ll be so glad to have the ability to relive these little moments again. Just remember that once you’ve gotten your photo, put that phone down and enjoy being present.

Scan And Digitize Old Photos

There’s a reason that when a house is on fire, the one thing people will try to save — after people and pets — is family photo albums. Our memories of the past are our most treasured possessions. And unfortunately, things like photos and slides aren’t made to last forever. They’re vulnerable to everything from floods, to fires, to the simple passage of time.

The best way to keep your memories safe is to scan and digitize your old photos and save them in the cloud or across multiple devices. There are great services out there, including our friends over at Legacybox, who can handle this entire process for you. If you’re interesting in tackling the project yourself, here are some tips for doing it at home:

Curate Your Phone’s Camera Roll

Having a smartphone in your pocket makes it a lot easier to document your favorite moments — and to have them automatically backed up to the cloud. However, as many people have experienced, the ease of documenting our lives can end up being too much of a good thing. It’s easy for the photos and videos of loved ones to get buried in your camera roll under photos of your latte, funny license plates you wanted to share with a friend, and screenshots of memes.

Having your photos buried in your camera roll can make them even more inaccessible than if they were hiding in that dusty box of old photos in the back of your closet. That’s why it’s important to get in the habit of regularly curating your phone’s camera roll — so you can clean out the stuff you don’t need and organize your favorite photos so they are easy to find and share.

Capture Their Story With StoryWorth

Although my dad is gone, I’m lucky enough to still have my mom. So when I recently came across an autobiographical storytelling service called StoryWorth, I had to give it a try with her. With Storyworth, you can send a different question to a loved one every week for a year, and at the end of the year, their answers will be bound in a book that you can keep. You can choose from a list of questions — like “What was your mom like when you were a child?” or “What was your first job?” — or you can write your own.

Using StoryWorth with mom has been an awesome experience. I love reading her stories each week and getting to know more about her life before she was my mom. And it means more to me than I can say to know that we’re having these conversations while we still have time, and that I’ll have this collection of stories and memories to treasure forever.

Comments