“Oh, Candice,” my grandmother said when I called her after moving into my dorm room for my first year at Ohio University. That phrase was a constant throughout my life. She would say it in celebration, joy, frustration, and sadness. It was flexible that way — the tone changing just slightly to fit the mood. It was only two words, yet it carried the weight of a whole conversation.

My grandmother and I were close that way. We could offer each other a glance, a small smile, or a simple “Oh, Candice,” and know exactly what the other was thinking. Our closeness was not bound by proximity or family size.

My grandmother (and the majority of my extended family) lived in Philadelphia and I was in Ohio. She was the mother to seven children — six boys and one girl, my mom — and the grandmother to over twenty grandchildren. But somehow, amidst all of that noise, we carved out a simple, tender connection that I struggle to describe but can feel growing in my chest even all these years later.

I had called her to check in. For as long as I could remember, my mom had scheduled weekly phone dates with my grandmother on Sundays. They would sit for hours and talk about nothing in particular, like only a mother and daughter separated by the distance of a job opportunity that was too good to pass up could have.

My mom would sit in the kitchen and talk as the world moved around her. My father grabbing coffee in-between work calls, my brother and I creating games out of the phone cord that was too long and slightly worn by time and impatient children. We moved in circles around her as she grounded herself to the chair in the kitchen, so many miles away from the woman who showed her what it was like to be a mother.

When their conversation would wind down my mom would shift the phone away from her face and yell, “Candice, Dylan — come talk to Grandmom!”

We would pull ourselves from different corners of the house and make our way to the kitchen where we would sit and share weekly updates of our lives. I’d recount school projects and sports reels and the birthday party at Castle Skateland where I held a boy’s hand during the slow skate for the very first time. This was our ritual. And so it only made sense to continue our calls when I left home and went to college.

“I think this place is haunted,” I said quietly over the phone as I attempted to fold my clothes neatly and place them away into the wooden built-in dorm dresser.

I said it quietly for two reasons. I was genuinely scared and felt that if I said it louder the “ghosts” would hear me and somehow it would get worse. And also, my grandmother was a devout Catholic and it seemed sacrilegious to be saying anything about it at all.

“Oh, Candice, what do you mean,” she whisper-yelled back to me.

An Italian woman of her age and frame only spoke in whisper-yells and real yells. She may have been 100 pounds soaking wet, but she had the bravado of a whole football team on the bus home from an unexpected win.

I then proceeded to explain to her that by “this place,” I meant both my dorm and Athens, Ohio as a whole.

Athens is known by some as one of the most haunted places in the world. There is just a feeling, an energy, in this place. You feel it in your bones when the wind blows leaves over the brick streets, in the stillness after they settle. It’s in the air — so much history crammed into such a small space. Every step retracing the well-worn path of previous inhabitants.

Much of this stems from the Athens Lunatic Asylum, a very old, looming, and now repurposed structure that overlooks Ohio University’s campus — think American Horror Story without Jessica Lang popping in to serve up looks and comedic relief every 25 minutes. There’s an angel statue that supposedly cries blood, a series of cemeteries that form a pentagram, and a list of dorms that were deemed haunted for various reasons.

My dorm, Washington Hall, made the top of that list. Rumor has it that a girls basketball team stayed in the dorm for a summer camp and perished in a bus accident on the way home. I can still distinctly remember the sounds that would come from the hall in the middle of the night — girls running up and down, dribbling their basketballs over and over and over.

So yeah, needless to say, I was freaked out and my grandmother was there to usher in calming words, reassurance, and a little bit of Jesus. She truly was a woman of faith and I was always a little bit amazed and confused by that. It was just something that I never really understood. I couldn’t seem to find the connection that she had.

When staying at my grandmother’s house, I would wake most mornings to her sitting in her living room on a big white couch in her white robe, sipping a cup of coffee, smoking a cigarette, and saying her prayers.

If I close my eyes, I can almost put myself there. I can feel the plush cream carpet under my toes, my hand tracing the metal banister as I walked down the steps to find her there. I would make my way over to an oversized floral armchair that I’ve since inherited and just watch her. She could sit in silence like that for hours, holding her prayer book that slowly became unbound and yellowed from years of early mornings and sleepless nights.

“I’ll say a Novena,” she said, which she knew would calm me. A Novena is like an ultra-marathon of prayer — a series of devotionals said using a rosary over the course of nine days. Although I never found myself to be religious, I had full confidence that she had a direct line to the (wo)man upstairs and I needed all hands on deck. She didn’t just pray for me, she prayed for all of us — children and grandchildren alike. She prayed in celebration, sorrow, and everything in-between.

The only things she wouldn’t pray for was the good stuff — love, luck, and money. I always tried to get her to budge on those, but she was steadfast on the power of the Lord and the things that mattered most when they would have their chats.

And so she prayed. And yes, it did calm me. But it didn’t stop the weird things I was experiencing. As I moved throughout Athens, to different dorms and eventually to apartments off-campus, I found myself constantly confronting the unknown. Door handles jingling, unexplained footsteps, cabinets swinging open by themselves — I had a diverse array of spooky occurrences. I’ve had strange experiences like this my whole life and always considered myself to be a bit more sensitive, but Athens took things to a whole other level.

Eventually, I graduated and, (a bit begrudgingly), left Athens. Of course, Grandmom was there to see me throw my cap.

“Oh, Candice,” she said with a smile on her face as I hugged her after the ceremony.

And then I was a “grown-up.” I went on to graduate school, married my college sweetheart, became a college instructor, and had a kid. Life happened. And somehow, thirteen years after I first called my grandmother from Washington Hall, I have found myself living back in Athens.

It only took three days after we moved into our new home for my daughter to start communicating with a spirit. Three days. To put that into perspective, at this point we were still using a towel as a bath mat in our bathroom because I couldn’t find the box labeled “curtains” that held the stupid bath mat.

I swore I would remember putting it in there as I reached the point of packing our house where you throw your hands up and all organization goes out the window.

It started out subtle — I would watch her eyes move behind me while I was talking to her or hear her giggle to herself while playing in her room. I could feel it, too. A presence, an energy.

We live in a big old house on a tree-lined street with other big old houses. It was built in 1900 and had character that comes with old homes that were built at a time when “proper women” forced themselves into corsets.

My leggings and Birkenstocks feel out of place walking on worn wood floors that have seen almost four times what I have in my lifetime. We moved into the near east side neighborhood, filled with families, made of professors and professionals, and the occasional undergraduate student that prefers a quiet street to house parties. We have enough space for our family to grow, a yard for our dog to play in, and, it seems, an extra guest as well.

“Laurel Bird, you need to lay your head down and go to sleep,” I said sternly to my two-year-old daughter as she sat upright in her bed. It was a generous 45 minutes past her bedtime and she hadn’t stopped looking at the corner of the room. There wasn’t anything there, save for a few stuffed animals and a set of wooden toy cleaning supplies that my best friend had gotten her for her first birthday. Then, she started waving her little toddler hand excitedly in that direction.

“Who are you waving to?” I asked timidly, unsure if I really wanted the answer or if I’d rather just live in denial that my little girl was moving into creepy kid territory at warp speed.

“I’m waving to Grandma,” she said sweetly, giggling to herself as she continued to wave. And then she started bouncing back and forth, almost as if she was dancing.

My grandmother could never sit still for long. She was a whirlwind in constant motion — usually with a cup of coffee in one hand and a cigarette in the other. My grandparents danced on bandstand in their younger years, and it always seemed like she was jitterbugging. She would stand by the furnace in their basement TV room, bouncing and bopping to a beat we couldn’t hear, warming her hands as she went.

On cleaning days she would blare Elvis throughout the house, crooning and swaying to the music in her worn sweatsuit, spraying Pledge as she swooped her dust rag over dining room furniture that held some of her most important memories.

When one of her kids or grandchildren called, she would rush excitedly to the phone and yell, “So and so is calling!” before grabbing the phone, sitting on the steps and enveloping herself in conversation with her proudest accomplishments.

She was barely five feet tall, but she would reach up as high as she could on her tiptoes to give you a kiss before you left, and then she’d run to the porch in the summers or the kitchen window in the winter to wave goodbye until you were so far down the street you couldn’t see her anymore. She moved in and through us.

In some ways she still is. Five years ago, I lost my grandmother to pancreatic cancer. It was soul-crushing. The type of pain that never loses its newness. I sit here at my computer typing this now, so many years later, with tears streaming down my face because losses of this magnitude never feel easier. They feel fresh and raw and sad always, I think. I feel her with me often.

Certainly in life’s large moments — like my wedding day which she tried and fought so hard to attend. She would tell the nurses and doctors while undergoing treatment that she just had to make it until May 28th, and they smiled kindly and sweetly, knowing she was nearing the end.

But more often, I feel her in life’s smaller moments. When I gave her eulogy, I quoted Nicole Krauss’s The History of Love, stating that she would fill “the space after the period and before the capital letter” of the sentences of our lives — and that has reigned true.

I think of her while drinking coffee out of her old Irish blessing mug, worn and coffee-stained. It’s imperfect and old and I can remember how her hands used to wrap perfectly around it while sitting in the early morning sun on her white couch, in her white robe, reading her prayer book.

I think of her every time I put on my favorite oldies station while cooking with my daughter. I hold her and we sway together like my grandmother and I did so many years ago. But mostly, I think of her while watching my daughter and my mom together.

After that night in my daughter’s room, I was completely overwhelmed. We had just moved into a new house and now I was genuinely afraid to be in it alone with my daughter. My husband is a chef and often works nights, which meant a lot of late nights together with just myself, Laurel Bird, and this “Grandma.”

I kept trying to get more information out of her, but every time I brought it up she would shrug her shoulders sweetly and laugh. I was getting frustrated. I couldn’t understand why she just couldn’t explain to me what was happening — and then I remembered she was two and forced myself to adjust my expectations.

Over breakfast one morning, my husband and I decided to ask her again.

“Bird, who do you wave to at night?” I asked as I picked up one of her mini-pancakes off the floor for what felt like the 800th time.

“Grandma,” she said nonchalantly.

My husband and I made eye contact. “Do you mean Mama’s Grandmom? he asked so quickly I couldn’t even decide if I wanted to know.

Without looking up from her breakfast she said, “Yeah!” excitedly, laughing and popping another piece of pancake into her mouth.

My husband looked at me, as if to say “I told you so,” and he had.

But I still wasn’t buying it. Plus, she was an agreeable two-year-old. How credible could she be?

The next day we left Athens to visit my Mom in Cincinnati. My daughter was so excited to see “her Mo” — a variation of my mother’s name, Maureen, which I decided early in my pregnancy would be her grandma name. Mo and Bird have a special bond that everyone can see, but that I feel deep in my bones. It is familiar and safe and, for me, a little sad only because I miss that connection with my grandmother so deeply.

When I returned to work three months postpartum my mom held my screaming, exclusively breastfed daughter for hours in an attempt to comfort her until I got home. She bounced and swayed and walked with her until my stubborn girl fell asleep. She has always been the first one on the floor with her, playing and laughing and giggling. They dance to old musicals in the living room and bake cookies and throw balls and go for walks to the creek.

When I say, “That’s my Mo,” to Bird, she screams, “No, that’s my Mo!” like it’s her battle cry. And she’s right. It is her Mo.

I walked into my mom’s house nervous to tell her about what had been happening in Athens. My mom and I don’t talk about my grandmother often because it makes us happy-sad. Happy to be able to remember a woman we both loved so dearly and to keep her alive through story and memory. But, sad because the end was hard, as endings usually are.

My mom was my grandmother’s primary caregiver as she battled pancreatic cancer and eventually entered hospice. She traveled to every appointment, blood draw, pharmacy run, and test. She called family meetings — sat quietly as we listened to doctors and nurses talk about my grandmother’s life expectancy in weeks and months when 30 days before we thought it’d be years. She carried the emotional weight of her grieving father, her six brothers, her own family, and she never complained. Not once.

When my grandmother became ill, I quit my teaching job at Kent State to be able to travel back and forth from Ohio to Philadelphia. I’ll never forget my mom walking me into the hospital after a particularly bad week and saying to me, “I want you to be prepared, Candice. She doesn’t look good.”

A mother trying to save her grown daughter from heartache in the hallway of a hospital is maybe one of the most selfless depictions of motherhood I’ve ever witnessed. So yeah, my mom and I weathered the loss of my grandmother together, hand-in-hand. And so to speak her name is precious and tender and something we do with care.

I couldn’t think of any way to lead into the conversation about my dead grandmother talking to my two-year-old, so I went in headfirst. “I think Bird is communicating with Grandmom in the new house.”

Her eyes got wide as she sat further back into her recliner. There was a silence-filled pause before she looked at me and said, “What?”

I repeated myself and to my relief she was genuinely intrigued. “No way!” she said with shock and curiosity.

I went on to tell her about what we had been experiencing in our home. The general feeling of a presence, my daughter’s interactions in her bedroom and throughout the house. I even shared how I walked into my foyer the week before and faintly smelled smoke. For many that might not be appealing, but for me it’s a smell of warmth and comfort that exclusively reminds me of my grandmother.

A few months after her passing, one of my uncles found one of my grandmother’s old sweatshirts and gave it to my mom and I. It was worn and stained and smelled exactly like her.

My mom sat in a chair, draping the sweatshirt over her lap. I laid my head down there and soaked in the smell of my grandmother. I wrapped the arm of the sweatshirt around my hand to get closer to the smell of coffee and smoke and a little bit of hairspray, tears streaming down my face as my mom ran her fingers through my hair.

After a brief minute to process what I had just told her, my mom popped up from her recliner, grabbed a large picture of my Grandmom and handed it to me. I accepted, knowing exactly what she wanted me to do.

I looked at my daughter and said, “Is this the Grandma you’ve been seeing in our house?”

Bird looked up at me and smiled. “Yes, Mama!”

My mom and I laughed with surprise and I repeated the question over and over and over again, unable to fully believe what she was saying. She said yes four times and no once, which I am going to take as a toddler perfect score.

The next day my brother came over and was in complete disbelief when I shared with him what happened. He grabbed the photo and asked my daughter, “Laurel Bird, who is this?”

“Grandma,” she replied without moving her red crayon off her coloring book. He looked up at me, eyes wide, but also warmed — I think it brought him comfort, too.

After my weekend in Cincinnati, we returned to our home in Athens. On our first night back, after getting my daughter down to sleep, I slowly slipped out of her bedroom and found myself in the dark upstairs hallway that had made me so uneasy just the week before.

I laid down in the center — legs up with my feet resting on the banister of the stairway down to our first floor. As a child, I used to lay like this in my grandmother’s living room, legs up high, arms splayed out. I would lie there and talk to her as she drank her coffee and read her prayers. And so that’s what I did, on the floor in the hallway of my home in Athens.

“Grandmom, if this is really you, and I hope it is, I want you to know I love you. I miss you so, so much. But if I am being honest, you are scaring the crap out of me. I want you to have a relationship with Bird, but can we please take it down a notch, because I’m going a little bit crazy over here.”

I sat there quietly, rolling my feet back and forth on the banister, half expecting to get a response back.

After a few minutes of silence, I began to feel guilty and thought to myself, “Candice, what are you doing? Your ghost Grandmom has traveled from the dead to spend time with your daughter and you’re asking her to calm down?”

It seemed silly and juvenile and unappreciative. I felt like I was turning away the one person I wanted back in my life so desperately. If she really was here, maybe I wanted her to stay? Could I hurt her feelings for asking her to leave?

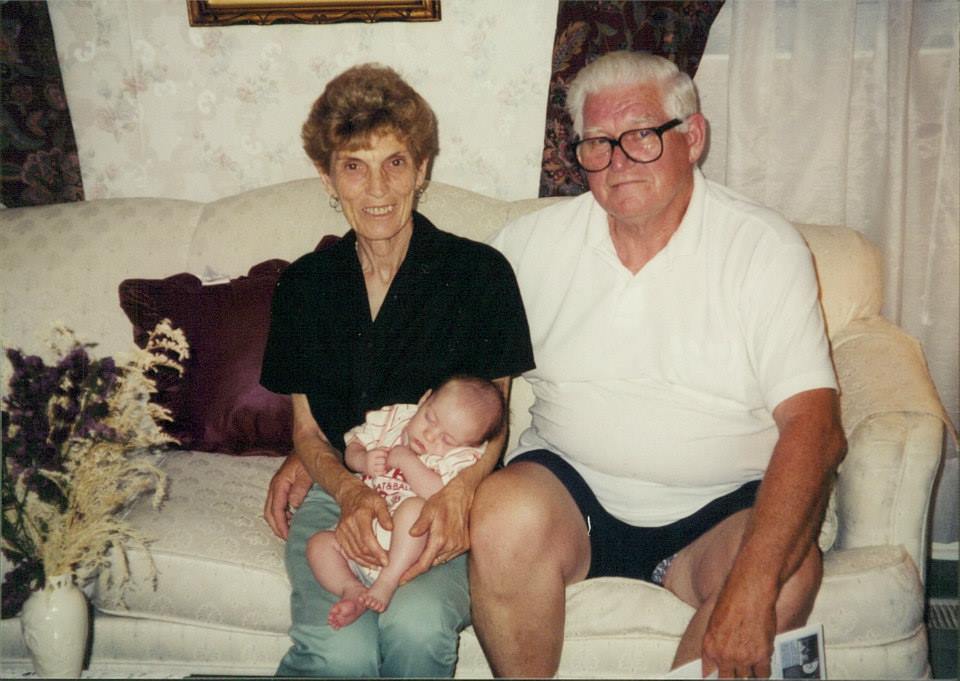

I had spent the past five years wishing over and over again that my grandmother could be here. That she could have been at my wedding and that I could have picked up the phone to call and tell her I was pregnant. I want to ask her how she thinks I’m doing as a mother and to see her hold my baby like she held me so many years ago. I would give anything to sit in that floral armchair in her living room in silence with her just one more time.

And then I laughed to myself — partly because I was lying with my feet on the bannister of my hallway contemplating the nuances of the afterlife and also because I already knew exactly what my grandmother would say. She’d say, “Oh, Candice.”

Comments