There’s a line in a Tame Impala song that chokes me up every time. That might sound like odd commentary about a band known for dancey, sometimes disco-tinged psychedelic pop but if you’ve ever lost a parent to an untimely death you would understand.

On the song ‘Posthumous Forgiveness,’ the band’s mastermind Kevin Parker sings wistfully to his late father, who died from cancer about a decade earlier, “I want to tell you about the time. I want to tell you about my life.”

This feeling – the innate desire to talk to a person you’ve lost – is one of the most enduring, stinging features of grief. No matter how much time passes, or how much you’ve healed, you will never stop wishing you could just… catch up, if only for a few minutes.

I can certainly relate. Fifteen years after my father died unexpectedly, I’ve more or less accepted his absence from my life. Still, I would give anything for the opportunity to sit down next to him and have a conversation. To ask him the random questions that have popped into my head over the years. To show him how crazy smartphones are. To tell him about my life.

I know my dad would be excited to learn what I’m up to these days. Not just because of the naturally biased curiosity any father is bound to have, but because of how closely my life, especially my career, has wound up mirroring his own. Somehow, I managed to turn some of the interests he passed onto me – writing, photography, technology, music – into an actual career that not only fulfills me, but also pays the bills. As my sister makes it a point to periodically remind me, dad would be thrilled.

In His Life: Remembering The Man Who Made Me

Tom Titlow, Sr. was, like me, a writer by trade. When he wasn’t churning out advertising copy in the smoky creative studios of some of Philadelphia’s most reputable ad agencies in the 1970s, he was doing something else his youngest son would also later love: taking photos.

More of a hobbyist than a professional photographer, my dad could often be seen with his Nikon FE2 film SLR slung around his neck in the 1970s and 80s, snapping photos at family functions, on the beaches of South Jersey and throughout the aesthetically eclectic, gritty urban landscape of Philadelphia. As his children gradually entered the world, they too would be captured within the silver crystals of 35 millimeter film – frame by frame, moment by moment. First came my brother Tom, then Joe, followed by Peggy and finally – despite my big sister’s attempts to convince me that I was adopted – yours truly.

It was my dad who bought me my first film-loaded SLR, the Nikon FM10, and showed me the basics of how to use it. And use it I did; In high school, I took that camera with me everywhere, photographing my friends’ bands and going on photo excursions to the city or down to the Jersey Shore. Then, as I pursued my journalism degree, I used the same camera to shoot assignments for my intensive photojournalism classes, just a few years before the school replaced the dark room and the distinctive smell of its photo-processing chemicals with a row of desktop computers.

I even occasionally shot my own photos for the stories I wrote for the college newspaper, which I dutifully clipped and mailed to my dad as they were published. With each new printed byline came an elated phone call or email from my dad, who always sounded more excited than I could wrap my head around. It was, after all, just the school newspaper. But to the man who would proudly hang my most horrendously incoherent drawings on the refrigerator when I was a kid, it was clearly a bigger deal than I could’ve realized.

I had only mailed my dad a few newspaper clippings before I got the proverbial dreaded phone call. My father, who had been expected to recover from the injuries he sustained in a recent car accident, as it turned out, would not recover. He gasped his last breath under the brutal florescent lights of a Florida hospital room and, just like that, he was gone.

“Dad Would Be Over The Moon”

The next few weeks – from the biographical photo slideshow set to The Beatles’ “In My Life” that we played at his funeral, to whatever the hell I was supposed to be focusing on in my journalism classes – were an absolute blur. Numb inside, I coasted along. Eventually, I somehow finished my degree. Along the way, even before I officially graduated, my career started taking shape as I took a job at the local alternative weekly newspaper and started freelancing for a few online publications. *It was happening,* I remember thinking incredulously. Despite the disruptive upheaval in the journalism industry during the mid-aughts, the thing I’d dreamed about in middle school was actually happening. I was becoming a writer.

As time melted on, my dad’s absence gradually settled uncomfortably into the landscape of my reality, eventually even fitting some vague definition of the word “normal.” Big life moments – from birthdays and Christmas Eve to graduations and family weddings – would never *quite* be the same, but day-to-day life more or less marched on and I accepted that the relationship I shared with my father had come to a close years prior.

Still, however normal the loss became, that feeling – the persistent longing for a chance to catch up – kept bubbling up from time to time. An entire decade after my dad died, I found myself wishing I could update him once again; I had just accepted a job as a staff writer and editor at Fast Company, a magazine he loved and, like so many other things, had introduced me to years before. If he thought a byline in the college newspaper was exciting, as my sister put it, “Dad would be over the moon” about this – if only I could’ve shown him the masthead.

My job as a reporter would land me in all sorts of interesting places, interviewing all kinds of smart, creative, and culturally notable people – a true dream job, if you asked me. Not once as a broke, overly anxious college student did I imagine that my career would take me to places like Abbey Road Studios in London, where in 2017 I toured the studios where The Beatles recorded and got an early listen to some of their newly-remixed classics, which it was somehow my job to write about. As I walked through the famed Studio 2 and snapped some photos in the control room, I knew the moment was a career highlight. But it once again took my sister to remind me of the larger significance. “Dad would freak out,” she told me on the phone. If only I could’ve called him, too.

As time and grief unfold together, this laundry list of “if only” conversations with the departed has a way of slowly getting longer. You can hear it in the aforementioned Tame Impala song when Parker starts amending the line “I want to tell you about the time” with actual examples from his own life. In his case, the list includes talking to rock legends on the phone, as well as a desire to simply let his late father hear the songs he’s recorded over the last decade. The first time I heard the song, however, I couldn’t help but be struck by one lyric in particular. In a bizarre, almost cosmic coincidence, he sings, “I want to tell you about the time I was at Abbey Road.” Yup. That’s the line that gets me.

Reliving Life Through Dead Media

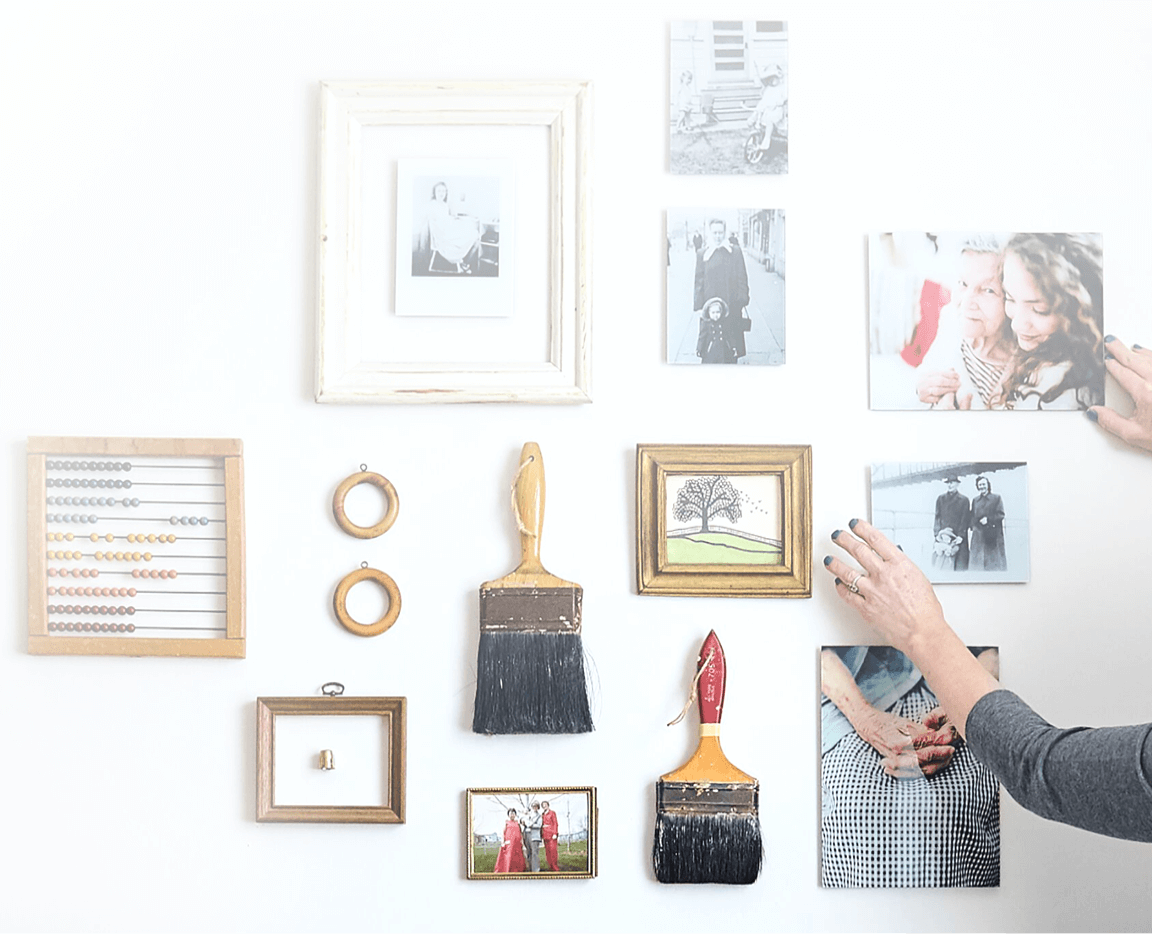

Shortly after that album dropped in early 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic ground reality to a halt. The record became a mainstay in my headphones as I tried to keep myself busy with freelance writing assignments and experimenting with analog photography on walks throughout the neighborhood. For me, the anxious stillness of quarantine inspired another time-killing activity: organizing and digitizing the photographs in the family archive.

When my dad passed away in 2005, I instinctively grabbed the box in his apartment labeled with the word “SLIDES” in black permanent marker. In the bleary-eyed, at times frantic effort to clean out a loved one’s living space after they’ve died, boxes like this can easily go missing or wind up in the trash. I knew that its label was shorthand for 35-millimeter photo slides, which my father would shoot on Kodak Ektachrome film throughout the 1970s and 80s. Maybe one day, I figured, I could get them scanned or even find one of those vintage slide projectors at a thrift store.

This box of analog imagery became part of my own archive of family mementos and personal artifacts, neatly housed in large plastic bins and carefully moved from home to home as life evolved and adulthood kept me too busy to ever bother sorting through it all.

When I finally cracked open the box, it revealed a treasure trove of forgotten imagery, each photo hidden away on a tiny translucent plastic frame just two inches wide. That’s the peculiar thing about slide photography; every image is like a secret you can only unlock by holding it up to light.

Scattered throughout the box were long lost memories, moments from my family’s history that never made it into the photo albums through which we had all nostalgically flipped countless times. These photos – of my brothers playing in a park as little kids, our mother captured beautifully by the natural light of a window, the grandparents we’d said goodbye to years ago – were like rare, unearthed outtakes from a movie we thought we’d seen in its entirety. Because they had been hidden away on this somewhat strange and inaccessible analog format, the photos were essentially forgotten. If my siblings and I had ever seen them, it was many years ago, brightly projected onto the wall of our dining room with the lights out. And because they were taken by a thoughtful photographer on a good SLR camera, they were of a superior quality to the family photos we’d seen a million times – perfect fodder for gifted photo prints.

These newly-unearthed family memories were a truly priceless find. But to me, the box contained something even more interesting and meaningful. Peppered throughout the boxes of slides were the photographs my dad took on his own time; the images he captured of subjects other than his own family. These are the photos that tell a deeper story about who the man was. Not only was he a proud father (which we knew), he was also a talented and creative photographer who saw the world through his own lens. And the way he looked at and captured the world, as these photo slides illustrated, was remarkably similar to the way I would many years later.

It’s almost uncanny. Jersey Shore beach scenery. Philly skyline night shots. Multiple exposures of neon signs. Close-ups of roses and other flowers. At first glance, a batch of scans from my dad’s photo slides could easily be mistaken for my own Instagram feed. By the time my dad introduced me to photography and the controls of a manual SLR, he was older, physically disabled and no longer shooting his own photos. We never talked about subject matter or content when it came to photography. He just showed me how to take long exposures and adjust the camera’s settings and sent me on my way. Little did I realize just how magnetically we’d be drawn to the same subjects, and even utilize the same techniques. Indeed, when I texted my sister a photo my dad had taken of neon signs in downtown Philadelphia, she assumed it was mine. Nope.

“So there,” I texted back. “I wasn’t adopted after all.”

As I scanned and retouched the photos from my dad’s slide archive, it almost felt like he was there with me. There was something gratifying about giving new life to his work, to photographs that were nearly forgotten. I felt like I was connecting with a younger version of my father I never knew, more of a peer than a parent, given that he was probably about my age when he took a lot of those photos. With each image, I felt like I was seeing the world through his eyes, following along as he told me a story I’d never heard before.

Fifteen years after I last saw him, my dad was showing me new things again. In its own way, it felt like the continuation of a dialogue that I thought had ended years ago. While it’s not the open-ended park bench conversation I’ve long dreamed about, it’s been illuminating to say the least.

Comments