Amidst the bustling boardwalk in Ocean City, New Jersey, there’s a real-life time machine. Surrounded by bright lights, busy crowds, and the nostalgic sounds of arcade games, it’s easy to overlook. But once found, you’ll feel a pull to peek behind the curtain. Step inside, take a seat, and get ready for a dazzling flash that whisks you to another decade. All it takes is **$3**!

Of course, this boxy, mechanical time warp won’t literally send your body back in time—indeed, when you step out of it, you’ll still be surrounded by futuristic lights and sounds as kids snap selfies with their smartphones—but for a few minutes, you’ll feel part of another era. That’s because this contraption, the analog photo booth nestled in the front of Jilly’s Arcade, is one of the only things on the boardwalk that’s been there for as many decades as it has. And its functionality—from its old-school chemical-and-paper-based photographic process to the paper strip of black-and-white photos that it spits out—has a decidedly old-timey feel to it. There are no filters or hashtags here; just a strip of printed photos that you can take with you into the future, like a postcard from a particular moment in time.

Analog photo booths like this are increasingly rare these days. As of 2008, there were only 250 chemical photo booths still operating in the United States, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Still, despite the proliferation of digital photo booths that are faster, easier to maintain, more cost-effective, and more aligned with our hyperconnected digital lifestyles, these old-school contraptions aren’t going away anytime soon.

As somebody who grew up coming to the Ocean City boardwalk and snapping a series of analog selfies with my siblings in the very same photo booth that still sits in Jilly’s Arcade, I have a special, nostalgic appreciation for these machines and any effort being made to keep them alive. Over the years, the boardwalk photo booth has become a bit of an annual tradition for my family.

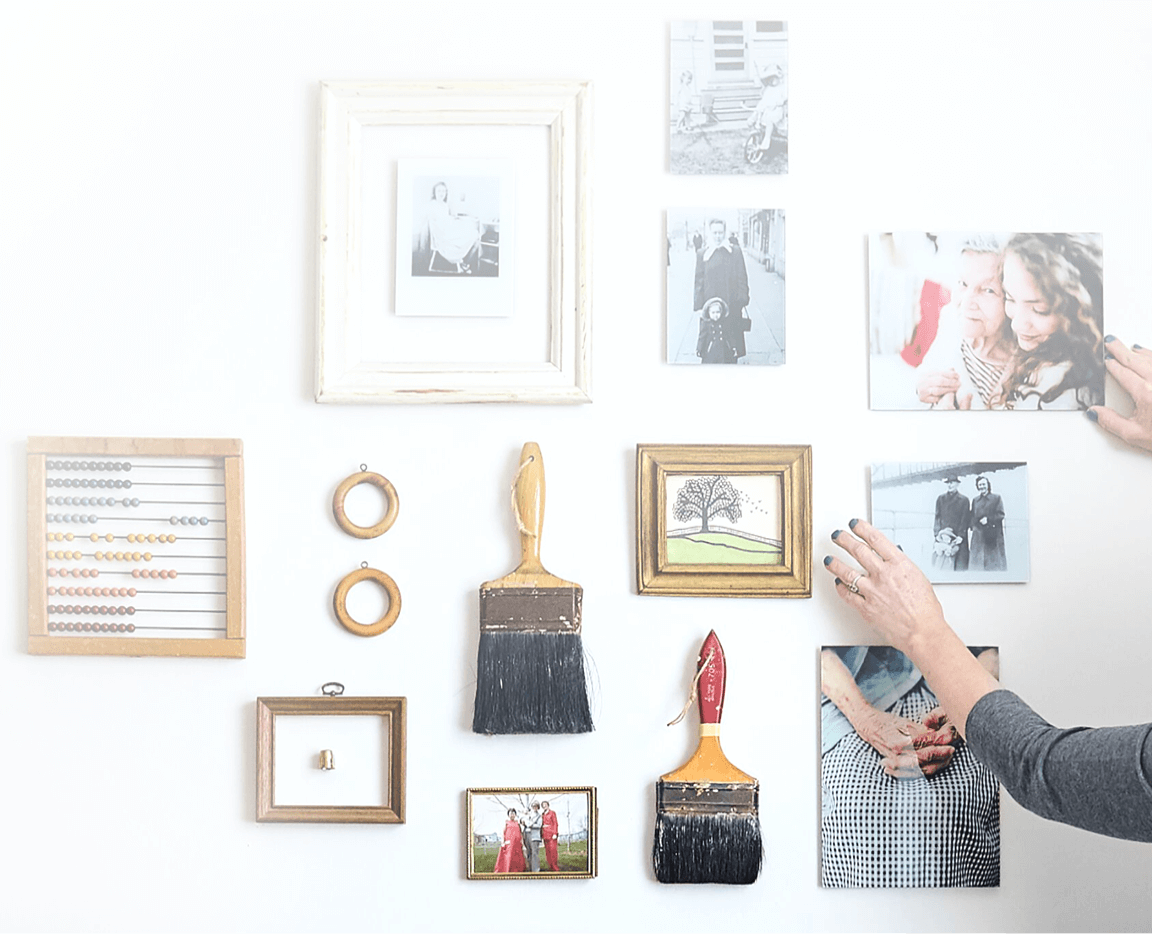

I still have photo strips taken with my mom and my sister when I was a kid in the early 90s, as well as a few others I’ve found that show my older brothers gleefully posing as little kids, making one silly face after another. One year, I even unearthed these old family photo strips, so I could scan the original images and arrange them in Photoshop to make new prints and give them to my family as Christmas gifts. To this day, any time I spot an analog photo booth, I make it a point to feed it a few wrinkled dollars and step inside.

We have people like Matt DeWalt to thank for the survival of these quaint photo-taking machines. DeWalt, along with his business partner Doug Ellington, runs a vintage photo booth company called Photomatica. In addition to renting out “vintage-inspired” digital photo booths for events like weddings and selling photo booths to bars and hotels—the part of their business that brings in the real money—Photomatica also acquires and restores authentic, chemical-based analog photo booths to help ensure these retro devices survive well into the future.

“There’s a certain magic about the old photo booths because it’s a machine,” says DeWalt. “It’s not just a high-end printer. Each photo strip develops. It takes two or three minutes. There are no digital copies.”

As magical as they may be to some, these analog photo booths are in no way an easy or particularly profitable business. As time marches on, the photographic technology employed by these machines becomes more arcane and specialized. The chemicals are still relatively easy to come by, but the unique photo paper typically used in analog photo booths is only made by a single company based in Russia.

Meanwhile, the technical expertise required to fix and maintain these machines is also endangered. “There’s almost nobody left alive that knows how to work on these machines,” says DeWalt. “It can be figured out, but there’s not enough money in it for anybody to really care.”

For Photomatica, the restoration and selling of analog photo booths is more of a side hobby than a cash cow. Still, for DeWalt and Ellington, the labor of love undertaken to help save these machines from extinction is well worth it.

A Brief History Of The Analog Photo Booth

The photo booth was born nearly a century ago when a Siberian immigrant named Anatol Josepho was awarded a patent for his first enclosed, automatic photo booth. In 1925, the Photomaton, as it was called, made its debut near Times Square in New York City, where lines of people frequently snaked around the block in the hopes of getting their pictures taken by this wondrous contraption. While similar technology was being toyed with as early as the 1880s, it was Josepho’s version of the photo booth that would first wow the public—and then serve as the blueprint for photo booths for the next 100 years.

The Photomaton was a hit. After drawing crowds with its first incarnation at 51st and Broadway, the Photomaton started popping up all over New York City and then across the United States. Before long, photo booths could be found all over the world.

For a mere quarter, regular people could sit down inside, be it alone or with others, and have a series of eight photos snapped and developed by an automated machine, which then spat out a strip of high-quality images within a matter of minutes. Before the advent of mass-market film cameras, photography was still a relatively inaccessible modern marvel. For some, the pictures taken inside these booths would be the only photos of themselves or their loved ones that they ever had.

By the 1960s, analog photo booths weren’t just ubiquitous; they were woven into modern culture. Everyone from John Lennon and Yoko Ono to John and Jackie Kennedy could be seen stepping into photo booths and, in the case of Lennon and Ono, incorporating the resulting photo strips into their art by including them on an album cover. Famously, Andy Warhol used the photo booths across New York City to photograph models and produce photo strips that would land on the cover of Time magazine, in exhibits at museums like the Robert Miller Gallery and The Met, and in a 1989 book titled “Andy Warhol Photobooth Pictures.”

It wasn’t just famous artists and world leaders who used and adored photo booths. It was primarily the masses. Indeed, much like digital photography and smartphones today, early photo booths had a way of democratizing photography and making it more accessible to regular people. For some, it was the only safe and comfortable way to be photographed.

“Early on, photo booths were the only place that gay couples could go and have their photo taken,” DeWalt points out. “There was no cameraman or dropping it off at the photo lab.”

Analog Photo Booths: From Near Extinction To Modern Revival

By the 1990s, the heyday of the analog photo booth was steadily winding down. First, the advent of mass-market instant photography from the likes of Polaroid made photo booths far less novel and exciting to consumers.

But the true death knell for this analog art form came from the same place it always does: digital technology. Almost as soon as they showed up, full-color digital photo booths started replacing the old school chemical photo booths in malls, arcades, bars, and anywhere else the vintage booths could be found. While the image quality wasn’t quite as pristine, these early digital machines were lightweight, easier to maintain, and faster than their analog counterparts. So from a strictly business perspective, the switch from analog to digital was a no-brainer.

Today, the logic of digital photo booths is even more compelling. The image quality is nearly indistinguishable from analog photo booths, which are increasingly cumbersome to repair, maintain, and move. Digital photo booths also let the subjects delete and re-take images and share them instantly via social media. And, of course, you still get a print of the digital images, even if they aren’t slightly wet with remnant chemicals from the old-school photo development process.

While they’re nowhere near as prevalent, analog photo booths are still out there in the wild. In New York, hip establishments like the Ace Hotel and dive bars in East Village proudly offer analog photo strips to customers and passersby. And for now, the photo booth on the Ocean City boardwalk is still spitting out analog black-and-white photo strips as it always has.

Each summer, when I find my way back to that boardwalk arcade, I make it a point to get a photo strip made with whoever I’m with, be it friends, a girlfriend, or one of my siblings—on the rare occasion that more than one of us is in town, we do our best to recreate the photo strips we posed for decades ago.

When our mother passed away in late 2014, we celebrated her life in a service in downtown Ocean City not far from where she spent some of her later years. Naturally, we found our way up to the boardwalk after paying tribute in a formal setting so we could do so in a more fitting one: inside the photo booth in Jilly’s Arcade.

At some point in the future, the boardwalk photo booth of my childhood will inevitably stop working. Maybe its owners will opt to track down a specialized repairperson or order the chemicals or photo paper required to keep it running. Or maybe they won’t.

In time, more of these machines will die off. But they won’t go extinct if DeWalt has anything to say about it. Even as digital makes more money, Photomatica continues to acquire and refurbish analog photo booths for its collection, including several different models of classic Auto Photo and PhotoMe photo booths. Some of these booths will get sold to business establishments and celebrities. Others, DeWalt says, may wind up in a museum-like exhibit he hopes to put together one day, complete with historic photo strips and other photo booth-related ephemera.

“One great thing about the old school ones is that you get that photo strip, and it feels like a little piece of history,” says DeWalt. “There’s something to say for that.”

Comments